Cinema Under Fire: Armenia

Turning back the clock

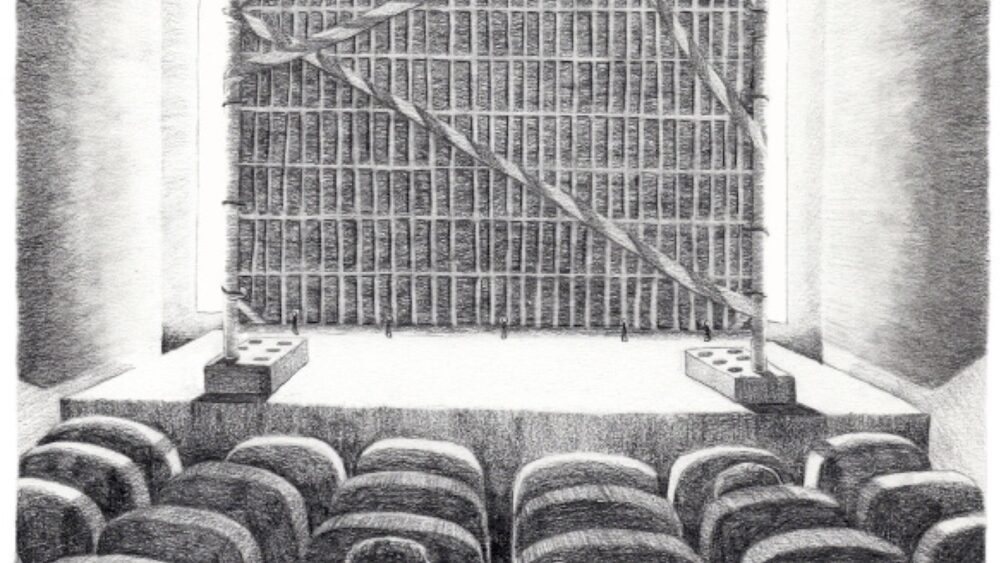

Illustratie: Sterre Meijerink (bewerkt)

What forces are threatening filmmakers’ freedoms? In a series of contributions from international film critics, Filmkrant reports on the political and economical forces at work on national film production and culture. This month: Armenia, where a proposed new law brings to mind the Soviet era.

The Velvet Revolution of 2018 brought changes across various sectors in Armenia, including the film industry. The main film funding body of the country, the National Cinema Center of Armenia (NCCA), under the leadership of Shushanik Mirzakhanyan, began revising the institution’s regulations by involving active film professionals and working in close collaboration with them. The new funding regulations came into force in 2019, and the first projects were awarded state funding shortly thereafter.

Despite the challenges brought on by COVID-19 and the Artsakh War, which led to a significant drop in funding the following year (previously amounting to € 900,000 and only restored to that amount in 2022), the film industry began to develop and recorded multiple cases of international success.

More Armenian films – and, more importantly, international co-productions – began to appear in the lineups of various film festivals across Europe. One of these, Aurora’s Sunrise (Inna Sahakyanm 2022), became the first Armenian majority co-production to receive funding from Eurimages.

The success was a result of mostly transparent funding procedures of the NCCA which used to be a cradle for incredible tales of bribery and favoritism dating back to Soviet times. The reforms helped restore trust among a new generation of local filmmakers, who, with a stronger institutional foundation, were able to attract European co-producers to their projects. Local festivals and co-production platforms further accelerated this momentum, for example, GAIFF Pro, the industry platform of the Golden Apricot International Film Festival, as well as initiatives like Eurasia.Doc and others.

One of the most urgent gaps to address in the Armenian film sector was the absence of a dedicated cinema law to regulate the industry. This was believed to be one of the reasons the country had been unable to become a member of the MEDIA strand of Creative Europe – a membership that could bring additional financial resources to film production.

After the creation of several working groups and the involvement of international professionals, months of collaborative work resulted in the adoption of one of two proposed drafts by the Armenian Parliament. Among the key reforms introduced by the new law was the dissolution of the National Cinema Center of Armenia (NCCA) and the establishment of its successor, the National Cinema Fund of Armenia (NCFA), whose primary mission is to support and develop the country’s film industry.

And while the industry was actively navigating this transition – reviewing and proposing new regulations for the newly established Fund – others were organizing, with the formation of professional bodies such as the Guild of Animators and the Guild of Documentary Filmmakers. In the midst of this, the Government of the Republic of Armenia released a draft proposal for amendments to the new Cinema Law, inviting feedback and consideration from the filmmaking community. Surprisingly, none of the active professionals in the field were invited to participate in – or even informed about – the government’s intentions to amend the law. The substance of the proposed changes presents an existential threat and a potential death blow to the entire industry.

The proposed amendments suggest changing the role of the Fund (i.e., the state) from that of a “supporter” to a producer and rights holder of the films. The revised article states: “The national body acquires property rights to films financed by it or through it, and may also carry out entrepreneurial activities related to film production independently or through another economic entity in which it has a shareholding or the ability to predetermine the decisions of its governing bodies, or to significantly influence their decision-making.”

In its justification for the revision, the government explains: “The current Law deprives the national body of the opportunity to have actual participation in the film production chain, limiting its role to that of a mere supporter. This hinders not only its effectiveness but also the implementation of long-term strategies in the sector. The proposed amendment provides the national body with the tools to participate in production processes, make investments, acquire property rights, and redistribute profits for the purpose of further financing.”

Thus, if the amendments are adopted, the NCFA will become the national policymaker, the sole source of public funding, a producer with the authority to interfere in production, the rights holder of the films it supports, and investor of profits – effectively transforming it into a commercial market player.

The suggested strategy is not a new one. It mirrors the way Hayfilm (also known as ArmenFilm, the predecessor of the NCCA) operated during the Soviet period and continued to function after the USSR’s collapse – up until 2018, when the regulations were revised and the NCCA ceased direct film production.

Needless to say, between the early post-Soviet years and 2018, the industry was deeply entangled in bribery and corruption, with only a limited number of films being released. During that period, the NCCA had the legal right to produce films and was exempt from paying VAT. According to persistent rumors, the institution’s previous leadership exploited this exemption to pressure filmmakers into producing their films through the NCCA – taking a cut in bribes while the rest of the money went into making the films.

Currently, Armenian cinema is truly under fire. The proposed amendments pose multiple threats to the industry. First and foremost, they violate several international conventions that Armenia is a party to – including the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD), UNESCO conventions, and the European Convention on Cinematographic Co-production, which Armenia joined in 2004. The amendments would halt all potential co-productions with Europe and block access to European funding sources such as Eurimages and Creative Europe, as these institutions only collaborate with and fund independent productions – those that retain the rights to their films and are free from political or institutional control. Moreover, Armenian producers cannot apply to these funds directly, as securing national funding is one of the core requirements for participating in European co-productions.

The proposed project would also open the door to administrative censorship and create a clear conflict of interest: by turning a public fund into a market player, it would shift priorities from cultural development to profit. In doing so, it risks destabilizing the entire film industry, exposing it to economic collapse, corruption loops, and other destructive consequences.

And although film professionals have consolidated their efforts to fight against the nonsensical project, many suspect the game is rigged. A few weeks ago, the amendment draft was published on the e-draft platform, where professionals could vote for or against the proposal. While the comment section includes over 30 detailed, critical responses from professionals outlining the potential harm the project could cause, something strange happened: at the very last moment of voting, the number of pro-votes suddenly skyrocketed to 175 – compared to 112 votes against. To this day, no one has publicly advocated for the new law, and the community is still left wondering who these phantom “supporters” are.

While the government stays silent on the matter and has not replied to any of the multiple emails sent by industry professionals, the management of the NCFA has invited a working group to finally discuss the proposed amendments. The content of the first meeting was not made public, but the team is now preparing for a second round of discussions – with hopes for greater transparency and meaningful dialogue.

Sona Karapoghosyan is a film critic and curator based in Yerevan. She is the co-founder of GAIFF Pro, the industry program at the Golden Apricot Film Festival, and has written for both Armenian and internationale publications. The analysis presented in this article is based on materials provided by the Armenian Unified Film Platform.